When the night came, the coyotes appeared from the desert, hovering like ghosts. Some of us turned over in our sleeping bags as if we could mute their yips and yaps by covering our ears, but everyone knows their cries go deeper than that. Hunger knows how to be heard. So we heard, heard the coyotes trot over the bunches of sagebrush toward the dead fawn we found earlier with the light of our phones, listened to the coyotes tussle and scream.

“Do you hear that death,” said Turnquist. He was always saying weird, dramatic shit like that. We turned over again in our sleeping bags, turned our thoughts back to the gold we’d find in the coming days.

But he wanted to be heard, too. He got up and yanked a log from the fire and yelled at the coyotes like an old, old man. He hurled the log and it smacked the ground and skittered across the dirt with red spurts of hot bark flying up like gore. The coyotes bolted, quieted. He tended the fire, moving logs here and there for a better, hotter burn. By the time he was back on his cot, they were at it again on the carcass, murmuring and yipping like little kids. We wanted to think of coyotes like dogs, but we hated them like this. Cruel in their desperation.

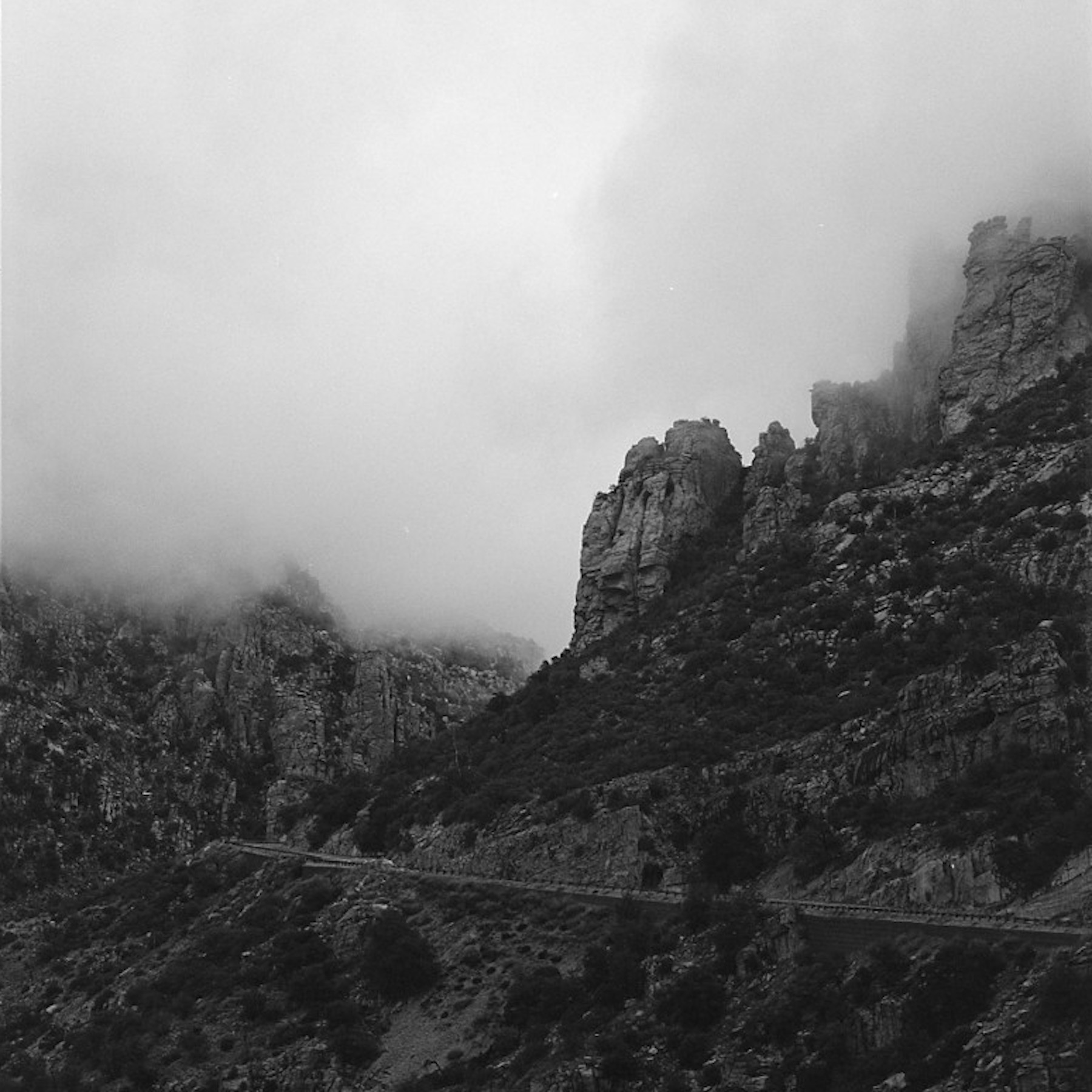

The next day we hiked through the valley. We tore up strips of smoked and dried elk and chewed on it until it was mushy enough to swallow. We were quiet, tired, and a little bored of all this antiquity. Annoyed, too, at the one of us who found this guy Turnquist. When we started to talk amongst each other, Turnquist barked at us to get along and admire the desert. We liked the desert, sure, but we also wanted to just get and see the gold he’d promised us. As we walked, the sun heated us and out in the sky, we saw there were boomers to the south. The masses of dark moved slowly along the mountain ridges, leaving a sluggish trail of rain. Turnquist made us camp early on a ledge above the valley, and we watched the lightning all along the sky strike out. None of us even recorded it on our phones, decided it was better to keep it to ourselves. That, and we were sick of Turnquist snarling at us and saying old man things like, “Not everything needs to be seen by your phones.”

Come morning, we were on the trail, twisting through old rabbit brush so tall it scraped our cheeks. Finally, we broke out upon a river snaking deep in the canyon. Our legs burned as we lowered ourselves, our pans and tools jingling.

Up close, the river was a blue we could not forget. We were flushed with blood, sweaty from the descent, and we took turns diving off the boulders into the water. We grabbed rocks and tried to sink to the bottom, but the water kept going, and we fought to not lose our breath. Eventually, we kicked down deep, opened our eyes and saw old mining carts, and we smiled and roared at each other. It was the loudest we’d been with each other all week.

Turnquist squatted on a rock under shade and sucked on the elk meat. “Get on with it,” he said, his voice low and gravelly, and we barely heard him. We were just boys at a river—a camping trip, we’d told our girlfriends and mothers. But Turnquist, of course, wanted serious work done. We obeyed. Took out our screwdrivers and plastic pans and white tubs and twine and donned our big sun hats so we looked like poolside housewives. For hours, we dug our screwdrivers into the slits in the rocks, scooped the dirt and crumbles into our pans. We moved the water over the river silt.

The old man yelped, stood, and pointed. Slowly, we realized. Then our voices called out, yipping and yapping at each other. The little flakes glinted and winked up at us in their dark silt. Gold! Turnquist sat back on his rock with the wickedest grin we’d seen on him. His serious work being done before him. We all tore into the rock, tore into it with hands, picks, and screwdrivers. We liked to think of ourselves as good men, but we were hungry for that gold, scraping and pulling the earth apart for it. We hated seeing ourselves like that, hated the desperation mirrored back at us. But we didn’t stop. “Do you hear that?” Turnquist said. Of course he saw us as we were.

Kylie Westerlind was born and raised in Reno, Nevada. She received an MFA in 2019 and has since been working on stories about neon cities in the desert. Her fiction has previously appeared in the Citron Review, Fearsome Critters, and Carve Magazine.