Pride Night in Paris, the Marais strung up head to toe with rainbow pennant flags, and you join some friends joining their friends. None French or—that you know—queer. Your thick-soled shoes are the only ones that haven’t covered you with blisters but, on the cobblestones, they prevent you from keeping up. That’s okay: in social settings, you prefer to tether like the tail of a lizard, able to release yourself at any sudden anxiety.

It is too warm for midnight. In the outdoor cafés, men’s bare chests glisten with sweat and gold glitter. You’re all walking two kilometers to the next bar because someone has decided to take charge, and this is where he is unapologetically leading. When you arrive, your shirt is bruised with sweat stains. Half the group goes in. The others finish bottles of wine on the curb. You really want a cold, cold beer. Inside, someone pays for your pint, which confuses you, the small stack of euros moistening in your palm. You eventually say thank you, which you fear comes across ungraciously. A girl with blue powder from eyelash to eyebrow sits next to you. She motions to a guy sitting at the end of the table in elbow pads, rollerblades on his lap.

Do we know this person? she asks.

I don’t know him, you shrug, though you don’t know her, either.

Bizarre, she says.

You introduce yourselves and you immediately forget her name. She rolls and unrolls a receipt like a cigarette and tells you that she is your age, from the middle of a Texan nowhere, somehow working as a concert promoter in Paris while you have yet to find a summer internship in the states and instead are overstaying your student visa, babysitting. The professor who did not need you to do research in the archives this summer does need you to watch his seven-year-old.

When she asks, you tell her no, you’re not seeing anyone. You left someone behind in a dusty California town. She wants to know more about him. Who was this boy? Why was he special?

You think of your sunny first date when you tried talking in the choppy ocean, but the current kept pushing you both apart until he finally put his arm around your waist. You think of giggling into each other’s necks. Of the book he gave you about Paris before you left, a note written for you in the first three pages. You remember thinking it read rather like a school assignment.

What happened? she asks. You start to think she is genuinely curious.

I moved to France. And there were other things.

Are you on good terms now?

You consider, checking your emotions the way you check knees and hands after falling. You find love’s bitter aftertaste has numbed, washed down by several months of French wine. I think we are, you say.

The world outside is half-dressed and spinning. You’re caught up in the spectacle of it—the dancing, the wigs, the bare breasts. A one-and-a-half-legged homeless man snoozes on the sidewalk, wet curls against his cheek, a pride flag gently tucked into his shirt pocket. The girl with the eye shadow slyly asks the others in the group if they know the rollerblade guy. She returns to you and confirms: he is not one of us. He isn’t talking to anyone but when you look at him he opens his mouth, he is missing several teeth, and gives a punctured smile.

The drag show, a rather predictable tribute to Whitney Houston, will not start for another fifteen minutes. The walls and floors of the club are a deep black, so dark you almost feel it touching you, like there are hands everywhere, and you all decide to wait outside. The group sits down in the small street overrun with cheery liberation. The girl in velvet takes out a bottle of twist-top wine from her bag and passes it around the circle. Some of you sing an ABBA song. A French girl leans in to ask for a light, hears your voices, and sings along for a few beautiful seconds.

Your group manages a good spot on the sweaty dance floor when the show begins. None of the Whitneys look alike, nor do they look like Whitney herself, and you quickly lose count of performances.

Among the throbbing bodies you fight the urge to stand near an exit, resist that primal sense of self-preservation you get in big crowds. A fear you aren’t proud of, but one that isn’t entirely irrational. You can’t help the world you live in. The grand finale is “I’m Every Woman,” and all the Whitneys, big and small, the beautiful and the less convincing, emerge on stage. They put their arms around one another, an embrace the crowd mimics. Then they each take small plastic bags out of their bras, filled with what you assume is baby powder, and spread it underneath their noses. At the end of the song, all of the Whitneys are sprawled out, dramatically overdosed, and despite the thunderous applause, the sticky clumps of powder on their chins fail to amuse you.

The drinks are much too expensive in this drag club so the group moves on with a collective urge to dance, put on pause when you pass a crêpe stand, the scent of luscious batter rising above body odor. In line in front of you is a very tall thin black girl with a tiny waist accentuated by her cargo shorts. You stare until you notice the note she’s written in Sharpie on her calf muscles, one word per leg: Fuck Off. You feel shame and wonder, if she is sexualized even by a straight young woman, what future awaits. You order grande frites.

In the next bar you happen across, Leo Sayer plays and people dance. You order another beer and carefully dance with it.

You notice, in this sticky crowd of sports bras and leather shorts and spray-painted hair, that the rollerbladed man is no longer with you. You note: the lizard releases the tail, not the other way around.

Waiting in line for the bathroom, you connect to the Wi-Fi. Even though Michael Jackson is blasting, you message him: Prince is on right now and it made me think of you. You send it before you let yourself think.

Gradually, the DJ switches to only songs without lyrics, as if everything has already been said, the words wrung out of the music, and the energy wanes. One boy leans in and announces: Not gay enough. He leads you all out to the curb.

Two women in black bras hold each other’s hips, staring at each other, smiles radiating. Their happiness throbs in your peripheral vision. Someone pushes you from behind, a glittered drunk woman, hunched like a witch in a fairytale. She flies to the couple and brazenly kisses each of them on the rear. You recognize their stupor. By the time they realize what she’s done the woman is already too far away. Their smiles spoil, as though they’ve been robbed.

Around four, you walk back to St. Germaine with your friend and a friend of hers, a boy you don’t know. You pass Notre Dame, who, when you first arrived in Paris, would remain lit up all evening, spilling dizzy light onto your wine by the Seine. Now, post-fire, she is surrounded by metal walls and scaffolding, like a cast for a broken arm. Your friend and the boy laugh intimately, and when she asks him for a piggyback ride, you drift behind.

When you get home you stand in the doorway. He’s responded to your message and you have to read it several times.

Mmm baby I remember how you used to squeeze my lemon.

This is the first thing he’s said to you since December. Although you have an early morning, you shower and brush and floss and trim your nails. You don’t know how to respond.

When you lie down, your gut turns as a memory bubbles to the surface: waking up in the middle of the night next to this boy, his face transfixed, washed in phone light, and at first your sleep-logged eyes thought the thrusting bodies on his screen were boats. Boats trapped in a storm.

In a sun-filled flat in the nineteenth, Ella tugs you up from a pile of pastel LEGOs.

Trampoline, she says.

You resent the idea of movement. On the terrace, the trampoline has been draped from side to side with pink scarves knotted into the mesh.

What is this? You jump as best as you can at a ninety-degree angle, your brain rattling.

Stop, she commands, you’ll wake the babies.

And then you see, the pink scarves are not decor, they are hammocks, and there are small plastic bodies inside them.

Ah, is this a baby castle? you ask.

She considers. Yes.

What do the babies do?

They sleep.

All day?

Yes.

Don’t they want to play?

No.

Do the babies work?

No.

How do they eat?

She shrugs. She hasn’t considered this question. They have food.

What if they run out?

You—once a middle class white child in a quiet California suburb—remember fabricating wildly popular games around disasters, starvation, shelterless winter, thieves. Your mother’s favorite game of yours had been called Famine, when you and your little brothers would prod the yard for weeds, dead leaves, sticks, fruits rotted like moldy eye sockets, and heap it into a massive pile to prepare for impending hunger. A game so pragmatic, Mother thought she had invented it. Though, hearing your jubilant cry of “Let’s play Famine!” must have rang a sour note in her ear.

Ella shrugs again. I dunno.

Then how is this baby castle going to sustain itself? you snap. Followed by another cheap shot: What do they do if bad guys come?—though this also has no effect on her. She has you tie another scarf along the wall, which hangs straight down. She goes behind it.

This is the shower, she says.

Did you paint her lips? you ask, picking up a doll. Neon blue eyes dart open, heart-shaped mouth a hemic red, candied eyelashes bobbing. You don’t remember dolls being so glamorous. At one point or another, yours had turned into muddy organ donors, their stomachs left snowing into the grass.

Ella goes chhh chhh chhh behind the scarf. Shower noises.

Maybe the shower is where you get superpowers, you suggest. She ignores you.

Ella, now freshly clean, comes back out. She commands you to wait there and bobs inside, running on the pink balls of her feet. She returns with her mother’s deodorant and a toothbrush and toothpaste. She takes another imaginary shower, this time to shave. The strokes along her tubby legs are so slow and meticulous that you chhh chhh chhh to remind her you’re there. Ella forgets the invisible razor in her hand and rub-a-dub-dubs her face, scrubbing fiercely at her skin. Finally, she looks back up at you, gilded eyes adjusting to the world around her.

She pretends to hand you the razor.

Careful, she warns. It’s sharp.

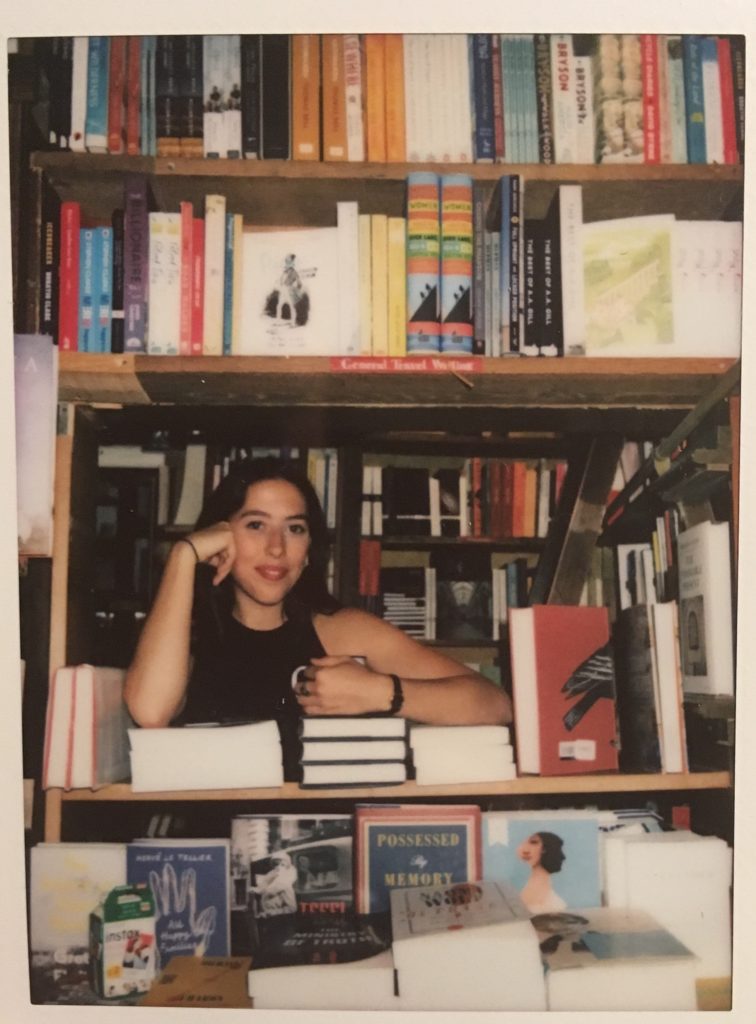

Julia Naman is a writer and musician from California. After studying Creative Writing at Pepperdine University, Julia moved to Santiniketan, West Bengal on a Fulbright Scholarship in 2017. She then moved to Paris, where she now lives. Earlier this year, Julia was a Tumbleweed (writer in residence) at the English bookstore Shakespeare & Co. She is a travel writer for Westlake Magazine, and her short story “Cheap Suit” won Honorable Mention in The Saturday Evening Post’s 2019 Great American Fiction Contest. She is working on her first novel.